Something deep and powerful and frightening

One man’s personal journey with the Church, from estrangement to reconciliation

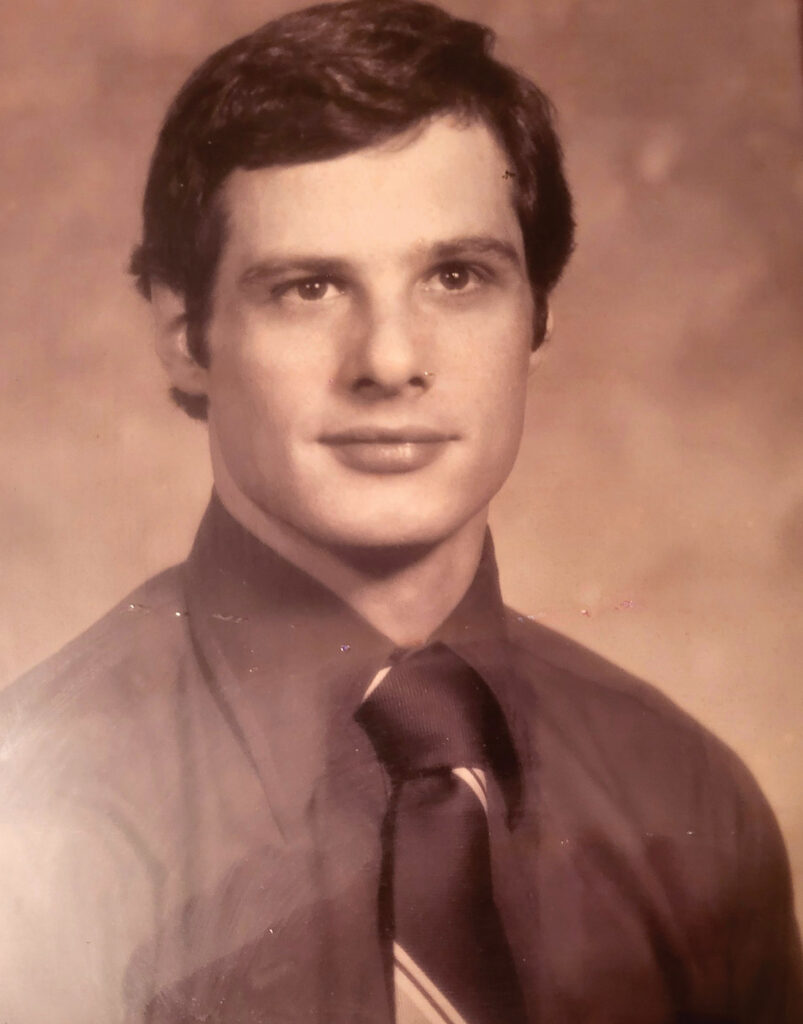

by Ed Oliver

In 1968, when I was twenty years old, I left the Catholic Church and began a twenty-year hiatus from Christianity and in some ways from God. It had been made clear to me that in the eyes of that Church the man I had been created to be was “unacceptable;” that the ways I expressed my love for another person were mortal sins and that my only hope for salvation was celibacy. Since I was already deeply in love and in a committed relationship with another man, I chose him and my true self over the church.

Over the next decade, my anger towards “Christians” and towards God grew to an actual hatred of organized religion and a deep bitterness, sadness, and woundedness where God was concerned. The little boy who loved Sunday School and said prayers every night; the shy, introverted and shamed teenager; and the young man who loved the liturgy, music and seasonal celebrations of the church were gone. In their place was a man who went through the next two decades with a hole in his soul, attempting to fill that hole with work; romantic “encounters;” and a repertoire of sarcastic remarks, jokes, and stories about the absurdity of religion.

Who needed the church and organized religion anyway. I had fled Mississippi as so many of my gay generation had done and was enjoying a wide circle of friends, a successful career and all of the benefits of living the “Rocky Mountain High” in Denver. There were restaurants and bars and discotheques; skiing and hiking; operas, symphonies and concerts in Red Rocks Amphitheater and an endless supply of handsome and available men. Who needed boring sermons, judgmental and self-righteous people who condemned you and televangelists threatening you with Hell’s fire just for being who you were.

Then in 1980 a dark and menacing force began to surface in the gay community, striking down young, beautiful and talented men as they shrank into cadaverous figures reminiscent of the inmates of the concentration camps of Nazi Germany. As the months and years went by thousands and thousands of gay men suffered cruel and untimely deaths, often rejected by their families and depending only on their partners and friends. It did not have a real name at first except for Gay-Related Immune Deficiency until science discovered the true nature of the disease and named it AIDS. By that time it was affecting other people with no connection to the gay community. I stopped counting when twenty-two friends and acquaintances had died.

For completely unrelated reasons at forty I moved back to Mississippi and what I found here was appalling. Yes, there were young gay men dying of AIDS but there were no care teams, support groups or assistance of any kind. There as not even a hospice until Whispering Pines Nursing Home opened a few beds to men in the last stages of the disease, most of whom were bedridden or nearly so. I did find there a place to volunteer but it was generally just to sit at the bedside and listen to the sad stories of men who had been abandoned by their families; who had no place to live; and men who were afraid they were going to Hell. Nice work, Christians.

By that time I had begun working with and become friends with a woman, Carol, who had been reared as a Southern Baptist but who had left that denomination and was attending an Episcopal Church. She had a beloved brother who was dying of AIDS with whom she was very close and she, like thousands of other sisters, was devastated.

Shortly after her brother’s death Carol told me that her church, St. Andrew’s Episcopal Cathedral, was forming an AIDS Care Team and she asked if I would want to join. At first I thought she was kidding…a church… a church in the South… was going to minister to gay men dying of AIDS? I had actually heard of dying men being surrounded on their death beds by family and church members begging for them to repent and be saved before they died. There was even one such case at Baptist Hospital in Jackson where that happened to acquaintance of mine.

I went to the organizational meeting of the St. Andrew’s AIDS Care Team and was met by genuinely kind and concerned people who were not out to convert anyone but only to provide what services they could to those in the Jackson area who, in fact, were dying. There seemed to be no judgement, no condemnation, no ulterior motive in these people; just a genuine desire to show compassion and love. I had fallen through the looking glass.

There were a few people for whom we began to deliver meals, visit, do laundry, take to doctor’s appointments and pick up medicine and I grew to respect and even like some of the team members. But, hey—a few weeks of that could not dispel decades of suspicion, anger and resentment.

Not too long after the formation of the team, a member of the team who was HIV+ developed full blown AIDS and died very quickly. It was a shock to everyone and Carol asked if I would like to attend his funeral at St. Andrew’s the next week. I had been to a few AIDS funerals in the past, both in Denver and in Mississippi and they were universally awful. The family of origin and the family of affiliation sat on opposite sides of the funeral home as most AIDS funerals were not allowed in churches and the minister would address only the family of origin with no mention of the deceased’s real family and who he really was.

I agreed to go as a sign of respect for “Bill” and I rode with Carol. When we pulled up in front of the Governor’s Mansion I was in disbelief. The entire compliment of four clergy were vested, there was a crucifer, torches, a full choir and a crowd of people. As a team Member I had never been inside the nave but only attended two meetings in the parish hall and as we sat in our pew I was impressed by the architectural beauty of the place, the stained glass windows, the beautiful music and the homily that actually addressed “Bill” for who he was, how much he would be missed and how much he was loved. This had to be a cult, I thought.

When it came time for communion, I did not want people to have to stumble over my legs or step on my feet, so I followed Carol up to the altar and took the bread and wine for the first time in twenty years. When I got back to my seat there was a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes. (My eyes sting and my throat tightens even as I type the memory.) Something had happened… something deep and powerful and frightening. Consequently, I did not go back for six months.

Eventually Carol told me that there was an Inquirer’s Class starting up in the spring on Sunday afternoons in the Chapel of St. Andrew’s. She didn’t insist that I go and told me that if I did go and didn’t care for it, I need never go back. The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

I basically threw myself into any group or ministry I could until one day about two years later I realized that I had been at church or at some church-related meeting or function five of the last seven days. I told myself I could not make up for twenty years of spiritual neglect in two years’ time.

I have been a member of St. Andrew’s now for thirty-four years. There were some disconcerting “situations” in the beginning such as when I first started serving chalice and heard “through the grapevine” that some parishioners would not come to me for communion because I was gay and probably had AIDS. For the most part, however, I have found genuine loving and caring people who love me just as I am and see no need for conversion or forgiveness for me just being who I am.

The only other echo of the past was after my father died in 1997 when I felt the call to be a Vocational Deacon in the church and asked the Dean to put together a discernment committee to guide me through the process to determine if the call was genuine or just a reaction to grief. I knew that at the time I would not be eligible for ordination because of the canons of the church but I wanted my church family to affirm or not that God was calling me to collared ministry.

The discernment committee submitted their findings to the Vestry. There were two parts to the report which was far from ordinary—a unanimous vote of 8-0 that my calling was, in their opinion, genuine; but by a vote of 6 for-2 they could not recommend to the Vestry that I be referred to the bishop because of my sexuality. I was not naïve enough to think that ordination was possible at the time but, still, I wanted my “family” to think me worthy of a collar.

As time has passed, much about the issues of sexuality and the Episcopal Church have changed. The church now ordains gay and lesbian deacons and priests and blesses and sanctifies the Sacrament of Marriage for same sex couples. In some small way I would like to think that my story has made that possible.

His disciples asked him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Jesus answered, “Neither he nor his parents sinned; it is so that the works of God might be visible through him. John 9:2-3